It’s clear how an issue like abortion engages deep moral convictions. By contrast, we often view economic matters as straightforward, seeing them in black-and-white terms without considering their moral implications. I would suggest, however, that economic and fiscal policy of the government has a profound moral significance. The Bible speaks more about God's concern for the poor and the oppressed than almost any other subject1, reminding us time and again that justice and compassion for the needy are central to living out our faith. It is very much important, then, that we evaluate the policy positions of the candidates for how they will help the poor.

To do so, we first need to understand the big problems plaguing our economy—inflation, debt, and labor force productivity—and how government spending is responsible.

Inflation

I recognize that the predominant theory in American politics, at least since the New Deal era of the 1930s, has been that a certain amount of governmental regulation of the economy together with a “social safety net” created by entitlement programs and government assistance is necessary to create a tolerable environment for the poor and the working class. Otherwise, those who peddle this theory argue, the wealthy would take the profits while the working class wallows in poverty.

One measure used to support this theory is to compare the poverty rate in the United States with and without taxes and transfers using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). The SPM Poverty Rate with Taxes and Transfers includes government programs like Social Security, SNAP (food stamps), tax credits, and housing assistance in the household's income. These benefits are added to a household’s resources, and taxes paid are subtracted to calculate the poverty threshold. The SPM Poverty Rate without Taxes and Transfers excludes the impact of taxes and benefits.

Theoretically, by comparing these two numbers, you can see how many additional people would be in poverty if it weren’t for those government programs and tax credits. The chart below shows that the poverty rate without taxes and transfers (represented by the small black line) has remained relatively steady, but has dropped slightly from 26.9% in 1967 to 21.7% in 2023. Meanwhile, the poverty rate with taxes and transfers (represented by the small grey line) has dropped substantially from 25.8% in 1967 to 10.5% in 2023. This has led to significant growth in the direct impact of government programs and tax credits (represented by the blue shaded area), theoretically decreasing the poverty rate by 10% over that time frame.

If that were the end of the story, it would be an absolute win for the idea that government programs can help the poor. The problem is that is not the end of the story. See the big green line on that chart? That’s the consumer price index, a measure of inflation (the rise in prices or decrease in the value of your money). You can see that inflation has consistently and significantly risen during the same time frame, outpacing the direct impact of government programs and tax credits. In fact, inflation has degraded the value of our money at roughly double the rate that government spending has, theoretically, decreased poverty.

When government spending outpaces the economy's ability to produce goods and services (i.e., outpaces GDP growth), it produces inflation. That’s because when the government spends excessively, especially through borrowing or printing money, it increases the overall demand for products and services. However, if the supply of goods and services doesn't rise to meet this higher demand, prices begin to go up, leading to inflation.

“Inflation is made in Washington because only Washington can create money…. The political process has been leading to Congress increasing spending, not increasing taxes, and financing the difference by the hidden tax of inflation.” - Milton Friedman

The problem is inflation typically has a regressive effect—meaning it affects lower-income households more than wealthier ones. Poorer households spend a larger proportion of their income on essential goods like food, housing, utilities, and transportation—all of which tend to rise with inflation—disproportionately reducing their purchasing power. Also, the poor typically have less room in their budgets to absorb higher prices and are less likely to have savings or assets that appreciate with inflation, unlike wealthier households who may own stocks, real estate, or other investments that can rise in value during inflationary periods, helping them to keep pace.

Inflation, then, actually increases poverty. Because the SPM Poverty Rate reflects how many people are in poverty after inflation is accounted for, it disregards the long-term inflationary impact of the spending created by these government programs. While families might receive more support today, inflation makes that support less valuable, increasing the amount they need to stay afloat. I would argue that this chart indicates the decrease in value has outpaced the increase in support. That means the programs meant to help the poor have caused more harm than good.

I think you all know that I've always felt the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the Government, and I'm here to help. - Ronald Reagan

Debt

This short-sightedness is a common element of the Keynesian economic theories which have guided much of our economic public policy decisions in the modern era of American politics. According to Keynesian economic theory, government spending increases demand for goods and services, encourages private investment, and furthers economic growth.

The general acceptance of this theory has paved the way for persistent increases in government spending over the last half century. In 1980, the total public debt sat at about 30% of GDP. Today, it’s 120%. To get an idea of what that means, take the value of every single product Americans make for the whole year. Add the value of every service Americans provide for the whole year. You are still 20% short of covering the national debt.

Here’s another way of understanding the scope of our national debt. Imagine that we were able to balance the budget completely, take 1/3 of our federal budget (the equivalent of the entire budget for Social Security and the Department of Education), and apply it toward paying off the national debt each year. Even in this fantastical scenario, it would take us more than 50 years to pay it off.

Critics of Keynesian economic theory, whom I find vastly more compelling, argue that while government spending can provide a short-term boost to the economy, it has negative long-term effects on economic growth. Increasing government spending leads to unsustainable levels of public debt. Over time, this accumulation of debt stifles growth by crowding out private investment, increasing taxes, and driving inflation.

High government spending, especially when financed through borrowing, also reduces the efficiency of resource allocation, as government programs are less responsive to market signals than private enterprises. This leads to a less dynamic economy in the long run, as private sector growth is constrained by higher taxes, inflation, and interest rates resulting from excessive public spending.

We’ve seen this drag on our economy, as anticipated by the critics of Keynesianism, play out over recent decades, as government spending soars to new heights. One of the most significant economic realities of the last decade has been the economic devastation caused by the coronavirus pandemic followed by the rampant inflation resulting from the government response to that pandemic. The reality, though, is that our economy has been remarkably stagnant for the last twenty years. The following chart shows that the average annual GDP growth during the last four presidential administrations (and five of the last six), regardless of party, has fallen below historical averages.

The bill on that debt is also coming due. We always talk about the debt as a problem for our children and grandchildren. Well, we are already paying for our parents’ and grandparents’ debt. I wrote a whole post about that here:

In that post, I pointed out that the federal government was forced to pay $659 billion in interest on the existing national debt in fiscal year 2023. That is $1,961.93 for every single person in the United States (including children). It’s more than $5 million per public school in the United States. It’s more than $1 million per homeless person in the United States.

For what we are currently spending on interest payments on our national debt, we could end homelessness in the United States. We could build a brand new state-of-the-art school building for every K-12 public school and still have enough leftover to pay every teacher a six-figure income. Or, we could just send everybody a check for nearly $2,000.00.

And it’s getting worse. As noted by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), in June, projected that annual net interest costs would total $892 billion in 2024 and almost double over the upcoming decade — rising from $1.0 billion in 2025 to $1.7 trillion in 2034, totaling $12.9 trillion over that period. According to CBO’s most recent long-term projections, interest payments would total around $78 trillion over the next 30 years and would account for 34 percent of all federal revenues by 2054. Interest costs would also become the largest “program” over the next few decades—surpassing Social Security (which is already set to become insolvent in the next ten years) in 2051.

Labor Force Productivity

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has actually reached record lows under the Biden administration. That is certainly a good thing as it means, for the most part, people who want a job can find one. But why isn’t the record high employment rate leading to improved productivity? It’s because the unemployment rate doesn’t tell us how many people are working. It tells us how many people can get a job if they want one. It does not include the people who are no longer actively looking for work. For that, we need to look at the labor force participation rate.

As you can see in this graph, the labor force participation rate, which had been steadily declining since the turn of the century, plummeted during the pandemic and has never fully recovered. According to the data published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 62.7% of Americans are working or actively looking for work. That’s the lowest it’s been since 1978. Hmm… 1978, what else was happening then? Oh yeah, that was right in the middle of the last inflation crisis, when CPI averaged an 8.74% increase annually from 1973-1982. That’s no coincidence.

Labor shortages produce wage inflation. As fewer people seek work, employers often have to increase wages to attract workers. Increased wages without an increase in productivity reduces the value of the money paid out. Alternatively, business can choose to simply decrease production. This reduces the supply of goods, which increases the price of those goods in the market.

To a large extent, the decline in the labor force participation rate is a result of demographic changes in our aging population. Still, studies show that welfare programs create a disincentive to work. That doesn’t necessarily mean that people just don’t work, but every time the government increases the money it hands out to people who don’t earn enough money to care for themselves—whether in the form of insurance subsidies, retirement benefits, food stamps, or otherwise—it forces employers to pay that much more to convince their employees to work more hours. It absolutely contributes to early retirements or people choosing to work less than full time.

Americans are demanding more and more money for less and less work. We can see evidence of this in the increased demand for remote work and flexible schedules, the fact that US labor productivity has slowed over the last 20 years2, and a series of high profile union strikes (including the United Auto Workers demanding 40-hour pay for a 32-hour work week). Last year, Gallup found that “quiet quitters”3 make up at least 50% of the U.S. workforce.

Ordinarily, these forces are self-regulated. There’s only so much money to go around. If the business pays too much money to labor without increasing productivity comparatively, the business fails. Eventually, employees learn to do what they need to do to get a job and keep it while employers learn to pay employees what is required to get them to work. The problem that we have is that politicians have realized they can fill in that gap by giving people the money they want without them having to provide anything of value in return. They pump more money into the economy that isn’t tied to any corresponding increase in wealth. That is the source of inflation. It is also why the growth of government inhibits labor productivity.

The Common Theme: Government Spending

Under the leadership of Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal, the federal government rapidly increased its expenditures during the 1930s and 1940s. Federal outlays were less than 3% of GDP in 1929. During the height of World War II, that number rose to more than 40%. By 1947, though, we had settled into a new post-war equilibrium at just under 14%. Since then, I would suggest we have gone through four eras of government spending.

From 1947 through 1979, we averaged federal spending of just over 17% of GDP.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected, ushering in an era of increased defense spending in an effort to spend the Soviet Union into oblivion. From 1980 through 1994, the federal government averaged annual expenses of just over 21% of GDP.

By 1992, the Soviet Union had collapsed, Bill Clinton was elected on a platform of fiscal responsibility and, in 1994, the Newt Gingrich-led Republican Revolution promised to reduce the size of the federal government. As a result, from 1995-2007, the federal government cut back its annual expenditures to around 18.6% of GDP.

Then, we hit the Great Recession in 2008 when the housing bubble burst. The federal government stepped in with large-scale stimulus packages, something that would later be repeated in 2020. As a result, from 2008-2023, average annual expenditures jumped back up to more than 22% of GDP during this era.

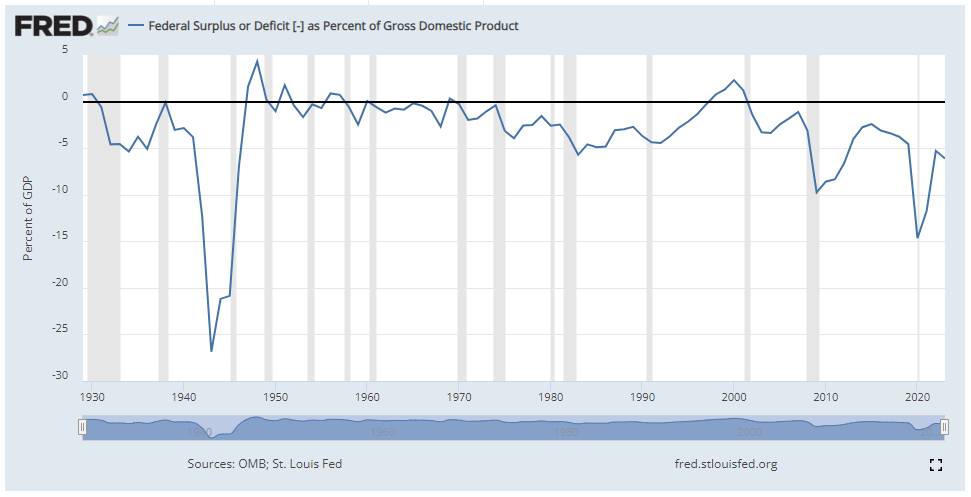

The interesting thing is that during all four eras, federal revenues remained largely the same, somewhere between 16.3%-17.7% of GDP. That means the government has consistently and increasingly spent more money than it has—that means debt and inflation. The chart below shows that, since the late 1990s, the federal government has operated at steadily increasing deficits each and every year.

In addition to running up the national debt, the enormous influx of cash injected into the economy in response to the economic crash in 2020 has resulted in a tremendous spike in inflation.

The Only Long-Term Solution

Every dollar our government spends comes at a cost. It can be paid for in three ways: taxes, debt, or inflation. With taxes, the government takes money directly from its citizens to spend it on what they it should be spent on. People don’t usually like that. Additionally, studies show tax increases reduce GDP too. So, tax increases are both bad policy and bad politics—unless you can claim the tax increase will only impact the “rich” or “corporations.” Then, it’s just bad policy.

All tax increases, regardless of who they are levied on, are ultimately paid by American consumers (including the poor). When businesses are taxed, they often pass the cost along to their customers in the form of higher prices for goods and services. This means that consumers bear the burden through increased costs of living. Similarly, if taxes are raised on individuals, it directly reduces their disposable income, limiting their purchasing power. Even taxes on high-income earners indirectly affect consumers, as their companies can cut jobs, reduce investments, or scale back operations in order to protect their purchasing power. This leads to fewer opportunities and higher prices for the poor and working class.

So, instead, the government can just spend the money without a tax to pay for it. Everybody knows this is bad policy, but voters don’t seem to care enough to make it bad politics. So, we continue to run up bigger deficits year after year.

That produces some combination of debt and inflation. Debt is paid by our children. Inflation is paid by everybody, especially the poor. They both create a tremendous drag on our economy.

The best and surest way to help the poor is to create an economic environment where they have the opportunity to succeed, generate wealth, and, in turn, produce more opportunity for others. That means we have to find a way to significantly cut government spending and unleash the American economy.

The best social program is a productive job for anyone who’s willing to work. Good economic policy allows businesses to thrive, creating jobs and lifting people out of poverty—not through government handouts, but through opportunity. - Ronald Reagan

Entrepreneurial capitalism takes more people out of poverty than aid. - Bono

From the dawn of history until the 18th century, every society in the world was impoverished, with only the thinnest film of wealth on top. Then came capitalism and the Industrial Revolution. Everywhere that capitalism subsequently took hold, national wealth began to increase and poverty began to fall. Everywhere that capitalism didn't take hold, people remained impoverished. Everywhere that capitalism has been rejected since then, poverty has increased. - Charles Murray

The Candidates’ Economic Platforms

In evaluating Donald Trump’s and Kamala Harris’s economic proposals, then, we have to start by asking how are they going to address our nation’s spending crisis?

Before we look at what they’ve said, let’s look at what they’ve done. Donald Trump’s four years in office saw an increase in federal spending over and above what we had seen during President Obama’s eight years in office4. Meanwhile, the Biden-Harris administration5 has furthered this spike in spending6.

Something else to consider is how Donald Trump and the Biden-Harris administration have responded to the 2020 economic crisis. Indeed, most of the debt produced in the last twenty years came as a result in spikes in spending in response to the 2008 and 2020 economic crises.

How would a Trump or Harris administration respond to the next economic crisis? Well, let’s look at their track records. You will recall that part of the response to the economic crisis during the coronavirus pandemic was three rounds of stimulus checks. Donald Trump was a big fan of this policy, advocating for higher amounts than what ultimately passed through Congress7. Meanwhile, perhaps the crowning achievement of the Biden-Harris administration is the Inflation Reduction Act (which Kamala Harris adamantly supports). Its answer to the economic crisis and persistent inflation was to spend roughly $800 billion on climate change and clean energy initiatives and health insurance subsidies.

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the candidates are now promising even more spending. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (a nonpartisan, non-profit organization committed to educating the public on issues with significant fiscal policy impact), conducted a comprehensive analysis of both candidates’ tax and spending plans. They determined that both candidates would likely further increase deficits and debt above levels projected under current law.

While I always get a little hesitant when people try to estimate the costs of tax policy (a reduction in tax rates does not necessarily produce a reduction in tax revenue8), it is absolutely clear that both candidates have promised significant increases in federal spending:

Kamala Harris

Extend and expand the Enhanced ACA Premium Subsidies ($550 billion)

Support affordable housing ($250 billion)

Improve border security ($100 billion)

Support manufacturing, research, and small businesses ($150 billion)

Expand access and funding for Pre-K and Child Care ($700 billion)

Establish national paid family and medical leave ($350 billion)

Support affordable and quality education ($350 billion)

Increase long-term care funding and support family caregivers ($200 billion)

Donald Trump

Strengthen and modernize the military ($400 billion)

Secure the border and deport unauthorized immigrants ($350 billion)

Enact housing reforms, including credits for first-time homebuyers ($150 billion)

Boost support for health care, long-term care, and caregiving ($150 billion)

That’s an extra $2.65 trillion in expenditures over the next 10 years under the Harris plan and an extra $1.05 trillion in expenditures over the next 10 years under the Trump plan.

How do they plan to pay for it? Kamala Harris intends to increase corporate tax rates, increase taxes on capital income, increase NIIT/Medicare Taxes, among other tax reforms9. First of all, it should be noted that those tax increases can’t come close to paying for all of the spending Harris is promising. Second, studies show that higher corporate taxes reduce wages most for young workers, the low-skilled, and women. This has led many economists to conclude that the corporate income tax is one of the most harmful and least efficient ways to fund our government.

Donald Trump, on the other hand, has suggested a few ways to fund his spending:

(1) tariffs, (2) reduce barriers to domestic energy production, (3) cut the Department of Education, and (4) reduce waste, fraud, and abuse.

The most significant of these methods is the tariff proposal. Quite frankly, tariffs are almost universally understood to be terrible economic policy. Tariffs are taxes on the American consumer disguised as protections for American jobs. Studies demonstrate that the costs of tariffs are almost completely passed on to U.S. consumers. This is not just economic theory, either. We saw exactly where this road leads with the Smoot-Hawley Act in 1930. While it didn’t cause the Great Depression, it most certainly deepened it, causing global trade partners to respond in kind with similar tariffs, destroying the global trade market.

The other three ways Donald Trump proposes to pay for his spending aren’t nearly as problematic, but are wholly inadequate to fund his promises, especially when he is sprinkling in promises to exempt tip and overtime income from taxation and end taxation of social security benefits—clear attempts to buy the votes of voters who have those kinds of income. There is no economic theory supporting those proposals; they are just good politics.

Donald Trump is then left only with the possibility that his energy policies, corporate tax cuts, and TCJA tax cut extension will be enough to fuel significant economic growth that is sufficient to pay for his spending. While that it is certainly possible, it still only helps insofar as it keeps us from increasing the deficit and going into debt faster than we already are. It is possible that his plan would prevent another explosion in inflation, but it is not going to address the rising interest paid on our national debt.

The end result is that neither Kamala Harris nor Donald Trump have a serious plan to address our spending crisis. Both administrations will continue to grow federal spending levels and continue to pass the buck on to our children. Meanwhile, the cost of our national debt will become more and more of a problem for our government and make it virtually impossible to balance the budget moving forward.

Who gets hurt by this the most? The people who need the government to be able to find away to fund Social Security when it runs out money in ten years. The people whose savings lose value when the next “crisis” triggers another spike in spending, fueling inflation. The people whose jobs are cut when businesses, facing higher taxes and rising costs, can no longer afford to expand or hire. It’s retirees and those already struggling to make ends meet who bear the brunt of a government that continues to pile on debt without a plan to rein it in.

In short, the poor. The poor will be hurt the most. I can’t accept that. It’s time that we demand our leaders put together a serious economic and fiscal policy plan that addresses our national debt and restores the United States as the land of opportunity. Unfortunately, neither Kamala Harris nor Donald Trump fits that bill. That’s yet another reason why I cannot vote for either one for President.

See, e.g., Leviticus 19:9-15, 25:35; Deuteronomy 15:7-11; 1 Samuel 2:8; Psalms 12:5, 35:10, 140:12; Proverbs 14:21, 14:31, 19:17, 22:9, 22:22-23, 28:27, 29:7, 31:8-9; Isaiah 1:17, 25:4; Jeremiah 22:16; Matthew 5:42, 19:21, 25:31-46; Luke 3:11, 6:20-21, 6:38, 12:33-34, 14:12-14; Acts 20:35; Galatians 2:10; Ephesians 4:28; James 1:27; 1 John 3:17

Specifically, average US labor productivity growth was 1.5% from 2004 through 2022, down from 2.9% from 1994 through 2004. That number grew to 2.7% in 2023, but that appears to be most related to a post-pandemic surge in new-business creation.

A “quiet quitter” is someone who is not engaged at work - people who do the minimum required and are psychologically detached from their job.

Federal outlays averaged 21.6% of GDP from 2009-2016. They averaged 22.9% from 2017-2020.

While I recognize that Harris can’t be held fully responsible for the actions taken by President Biden while she was Vice President, she has said that she would not have done anything differently than him.

Federal outlays averaged $25% of GDP from 2021-2023.

The theory here is quite simple. Tax cuts can spur additional economic investment and growth, which can increase the base of the tax, thereby increasing tax revenue even as the tax rate is reduced. The best case study of this principle is from the 1920s, when President Calvin Coolidge and Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon engineered a staggered reduction in the top marginal tax rate from 73% in 1920 to 24% in 1929. During the same time frame, taxes paid by that group more than doubled (from $300 million to $700 million). cato.org

The first round of checks were a product of the CARES Act. In his remarks upon signing the bill, Donald Trump bragged repeatedly about passing the “biggest ever” stimulus package. While Trump expressed concern with the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 which produced the second round of checks, his concern wasn’t so much the total cost - he actually said the $600 amount for the checks was “ridiculously low” - but that there was too much money going to foreign aid. In fact, Donald Trump repeatedly pressured Congress to approve $2,000 stimulus checks.

At the same time, she plans to extend the TCJA tax cuts for households making less than $400,000 and expand the child tax credit and earned income tax credit. Under the CRFB’s analysis, it should be noted that all of the projected revenue from all of the increased taxes are completely offset by the projected reduction in revenue associated with those tax cuts.